Templates explanation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Mention the term "Local template".) |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

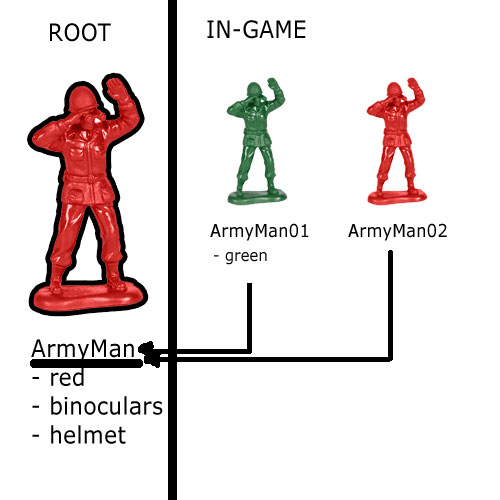

[[File:Rootsarmy.jpg|frame|Army Men game has 2 roots: ArmyMan and Tank. Thanks art team!|none]] | [[File:Rootsarmy.jpg|frame|Army Men game has 2 roots: ArmyMan and Tank. Thanks art team!|none]] | ||

== Local instances == | == Local instances/templates == | ||

You never really place a root in the game. You place a reference to the root in the game. Roots really exist on another plane outside of the game. | You never really place a root in the game. You place a reference to the root in the game. Roots really exist on another plane outside of the game. | ||

The game merely contains links to the root. When you drag a root into the game, it creates a local instance of the root at that spot. You could say local instances are children of their parent (the root). | The game merely contains links to the root. When you drag a root into the game, it creates a local instance (also called local template) of the root at that spot. You could say local instances are children of their parent (the root). | ||

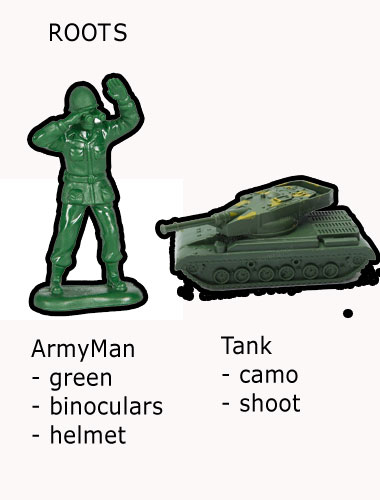

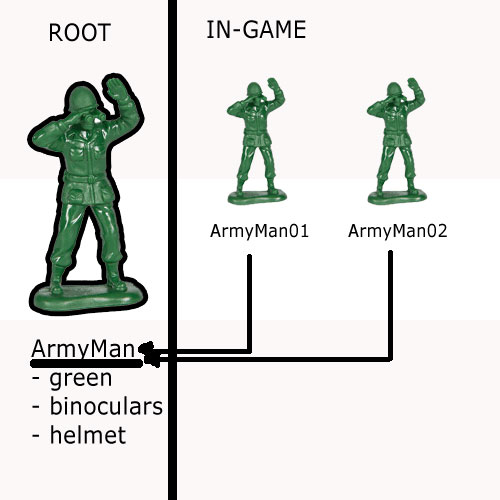

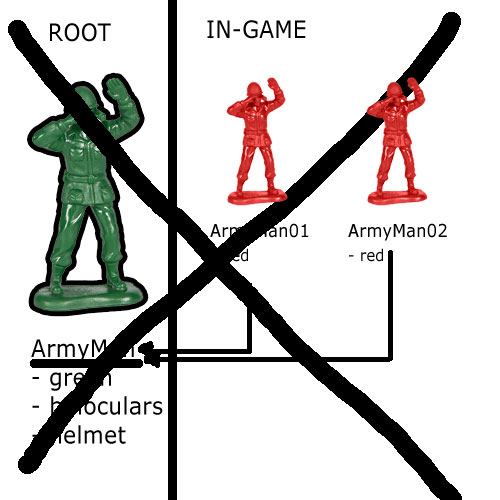

[[File:Localsarmy.jpg|frame|Army Men game has 2 local instances in-game that refer to the root ArmyMan.|none]] | [[File:Localsarmy.jpg|frame|Army Men game has 2 local instances in-game that refer to the root ArmyMan.|none]] | ||

Revision as of 08:16, 1 August 2017

Root template

Root templates are the building blocks of our game. A root template can be an item, a character, a trigger, etc.

A root template describes a game object. It contains the data of a thing necessary to put that thing in the game. (For instance: its visual, the physics, the AI bounds, name, stats, scripts, etc. All these properties describe and make up the game object.)

A root template is set up so that it defines the default visual and default behaviour of the game object. This means that a root template contains important gameplay information.

For our interactive, reactive, systemic game to work correctly, we need roots and they must be carefully set up.

Local instances/templates

You never really place a root in the game. You place a reference to the root in the game. Roots really exist on another plane outside of the game.

The game merely contains links to the root. When you drag a root into the game, it creates a local instance (also called local template) of the root at that spot. You could say local instances are children of their parent (the root).

A local instance can live without data. It just refers to the root and it will get its data there.

However, if the root is deleted, the link is broken and the local instance will no longer be able to show anything. (This is why you get asserts if roots are deleted when they’re used by local instances.)

Inheritance

If you are an artist, think of a root template as a magical mold or a magical pattern: when you update the mold, everything you ever made with it updates too!

If you are a programmer, think of a root template as a class.

Every time a root template is updated, all its local instances inherit the updates automatically.

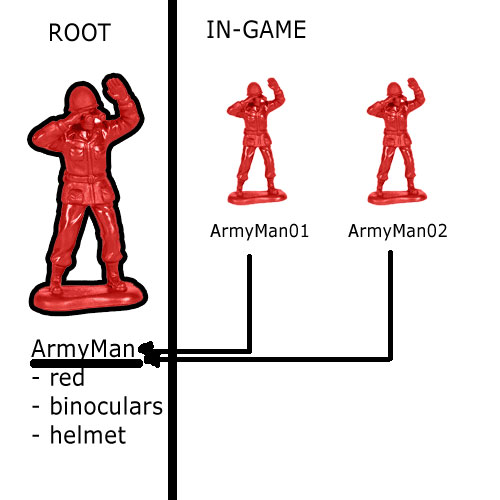

| “Green?! NO! All ArmyMan must be red!” The Root ArmyMan was updated with the colour RED. All its instances in the game everywhere inherit the colour automatically.

(NOTE: This is just an example of a property. Colour works differently in our game.) |

Whew. What a relief. I thought we would have to update all local instances everywhere in the entire game. Thank you root system!

Examples:

All hail roots. |

Consistency and player expectations

By using roots, we also ensure consistent behaviour of the items in our world.

Examples:

|

The player of our game has certain expectations. Things do what they look like they do in real life:

- you can read a book,

- you can drink wine,

- you can eat bread,

- you can cook meat,

- you can climb stairs,

- you can open a cupboard,

- you can open a door,

- you can open that hatch,

- you can open a can of whoop ass,

- you can wear a helmet,

- you can put on shoes,

- you can use that weapon on the wall,

- that shield is not just decoration,

- you can wield that broom as a weapon,

- you can look in that mirror,

- you can cook something in the oven,

- you can lie in a bed,

- you can sit on a chair,

- you can climb a ladder,

- ...

You can move everything that is not too heavy and not nailed down.

You can pick up anything that looks like it can fit in a backpack. (Exceptions: barrels, crates, chests, baskets, a lot of weapons and armour.)

You can interact with things that you expect to be interactive and see an animation (turn on a lamp, pull a lever) or hear a funny remark (click on a gravestone) or you can do an item combo with it (an anvil, an oven).

To live up to these expectations, we set up the roots correctly, and as a result, all its instances inherit the settings and everything works as it should. If one item in the game behaves differently, it is experienced as a bug and it’s not the way this game was designed.

What is wrong

If you turn off or change this expected, standard behaviour on a local instance, that is wrong in 99% of the cases: it is no longer consistent with the other items of this type and confuses the player. It’s a bug, it’s an inconsistency.

What is even worse is to set up such behaviour on a local instance. Doing this is wrong in 99% of the cases: it then only works on that local and not on the rest of its brothers and sisters. This is not consistent and you are not using the power of the root system.

“Green?! NO! All ArmyMan must be red!” The WRONG way to do this is to go over every local instance and override their colours. This is wrong because:

|

Overrides on local instances

A designer or an artist building the world can override properties of game objects. Because sometimes, there are exceptions and then overriding a property is a powerful tool.